EU-China: Drop the Masks, Back to Real Diplomacy

In

Diplomacy in 2020 was mostly about shifting the blame and creating distraction.

China’s “mask diplomacy” sought to portray the People’s Republic as benign and effective. The world and, more importantly, its own citizens were to forget its careless disregard for human life and its initial obfuscation of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan. Russia too engaged in “mask diplomacy” at first (and the usual disinformation) before discovering that a pandemic is a symmetric crisis: it spares nobody.

Read the full text below.

This article was first published on Forum.eu

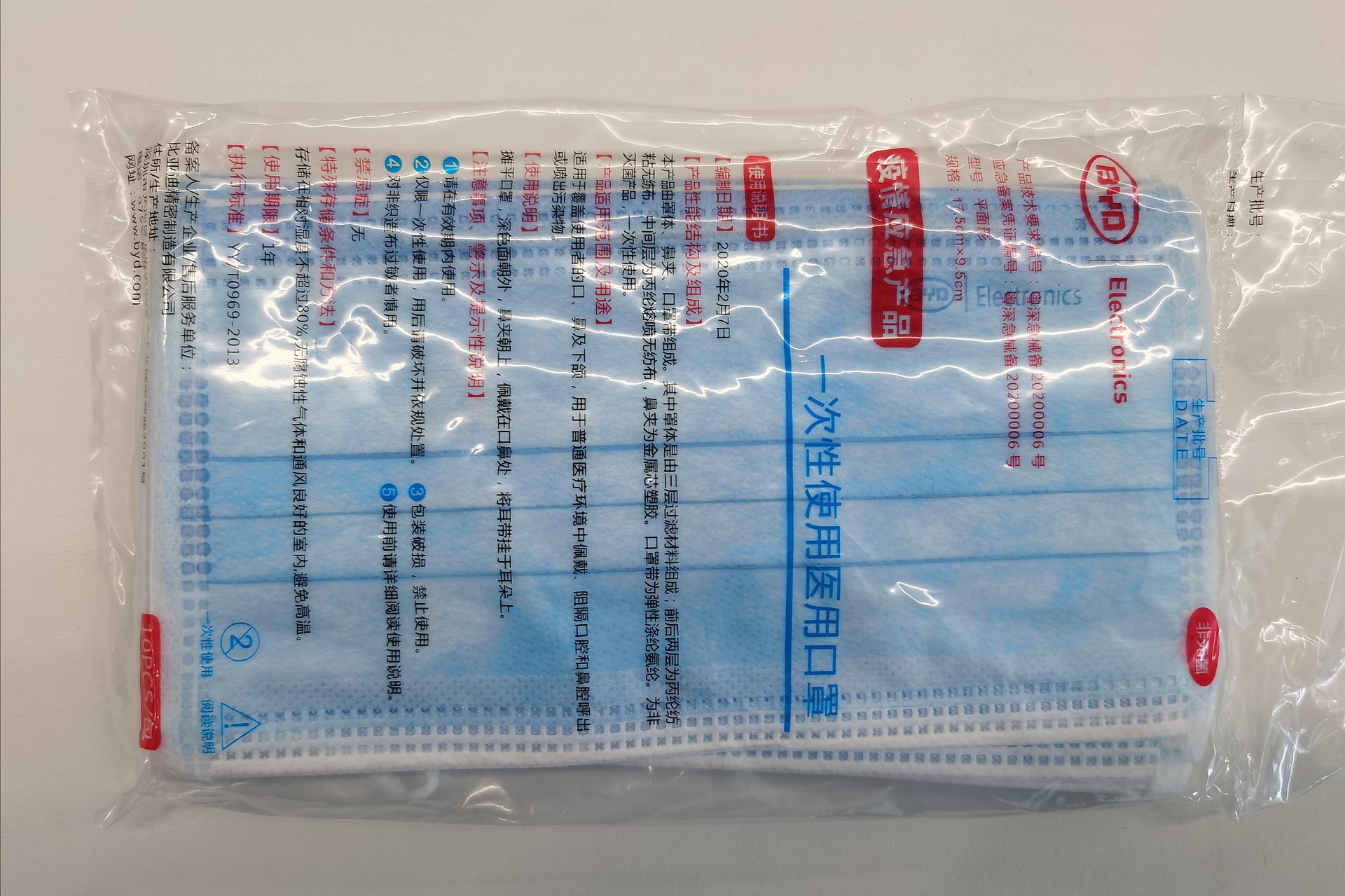

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

*****

EU-China: Drop the Masks, Back to Real Diplomacy

Diplomacy in 2020 was mostly about shifting the blame and creating distraction.

China’s “mask diplomacy” sought to portray the People’s Republic as benign and effective. The world and, more importantly, its own citizens were to forget its careless disregard for human life and its initial obfuscation of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan. Russia too engaged in “mask diplomacy” at first (and the usual disinformation) before discovering that a pandemic is a symmetric crisis: it spares nobody.

Not even Donald Trump, but once cured himself, he seemed to consider the problem solved. A series of new sanctions against China in his last weeks in office had to convince Americans that they must worry more about Beijing’s evil designs than about the pandemic raging in their midst. Effective corona measures will have to wait until after Joe Biden’s inauguration on 20 January. Only the EU was too caught up in its internal negotiations to try and put the blame on someone else.

After the masks, 2021 risks becoming the year of “vaccine diplomacy”. One cannot blame any government for aiming to inoculate its own citizens first. But the West cannot have it both ways: pre-ordering the entire production of Europe- and American-made vaccines well into the new year for its own use and being surprised that other countries start administering Russian and Chinese vaccines. (While India, Iran, Vietnam, and others are close to producing their own).

Vaccination should not become a tool of great power politics – not when people are dying. It doesn’t matter whether the cat is black or white, said Deng Xiaoping, as long as it catches mice. Likewise, it doesn’t matter who makes a vaccine, as long as it is safe and effective. None of the great powers, in fact, can make sufficient vaccines available to pose as saviour of the world. Would it not be better then to coordinate through the World Health Organisation (which Biden committed to re-join) and make sure together that the worldwide vaccination campaign is rolled out in the most efficient way?

Effective cooperation on vaccination could contribute to better relations overall, and create opportunities for real diplomacy.

In this sense, the EU and China started the new year well (and early) by announcing, on 29 December 2020, a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). Brussels and Beijing have been negotiating this agreement, which is still to be ratified, for seven years, yet now some suddenly have second thoughts.

The EU ought to have waited for Biden to take office, runs one argument. That seems to suggest that the EU must earn Biden’s confidence. I would say that Biden must work to restore Europe’s confidence in the US. Asking the EU to submit its China policy for approval hardly seems a good start.

Negotiations on this agreement started when Obama was still president. If the EU had to fear a strong reaction from the US, it would have been from Trump. His idea of diplomacy resembles that of the Mongol khans as once described by the historian Steven Runciman: “His friends were already his vassals; his enemies were to be eliminated or reduced to vassaldom”.[1] With an agreement in principle now in place, the EU can argue that an approach of what I call “cooperate when you can, push back when you must” delivers results, unlike Trump’s confrontational policies. That puts the EU in a much better position to coordinate with Biden and design a China strategy that is firm enough to block any illegitimate use of China’s power, but accommodating enough to avoid a rivalry without end.

That will, of course, require a balanced diplomacy on China’s part too. Having actually been ruled by the Mongol Yuan dynasty itself (from 1271 to 1368), China should refrain from seeking to impose vassaldom on anybody else. Some see the CAI as creating a split between Brussels and Washington. But if that was China’s objective, it ought to have acted much earlier, when the Europeans were still shell-shocked by Trump launching a trade war with China and adopting sanctions against themselves. China was too focused on the US, however, and too dismissive of the EU, and wasted what might indeed have been an opportunity to drive a wedge between the two. Now it is too late: every single European is eagerly looking forward to work with the Biden administration.

The CAI will create more reciprocity in market opening, as the EU has been demanding for a long time. Many point out China’s poor track record in implementing treaties. Brussels will have to be very firm, therefore, and make it clear that non-implementation of the CAI will result in reducing the EU’s own openness to China. That applies anyhow to the products of forced labour, which cannot enter the European market in any way whatsoever. But some critics act as if they discover only now that China is an authoritarian state and see that as a reason to reject the agreement. The CAI will not undo China’s authoritarianism, indeed, nor, alas, could any treaty. China can be forced to compromise in its relations with other powers, but as a great power it can per definition not be coerced into changing itself. But the CAI will ensure that the EU too will stay true to itself and that, as it trades and invests in China, it does not itself become party to human rights violations.

This EU-China deal is not a great victory for human rights. It is also not a one-sided victory for China. It is a victory for diplomacy. There are worse ways to start 2021.

Sven Biscop has zoomed in and teamed up online when he had to, but has resolved to boycott virtual meetings as soon as possible in the new year.

[1] Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades. Volume III: The Kingdom of Acre. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1954, p. 248.