EU Dependence on Russian gas: There is no short-term alternative

In

The EU wants to break free of its gas imports from Russia. US natural gas was offered by Washington as an alternative. T. Zgajewski shows that the implementation of this ambitious project will be difficult to carryout, at least in the short-run.

*****

The EU–US Summit was held in Brussels on 26 March, 2014. The issue of energy dominated discussions, which sought ways to end EU energy dependence on Russian gas. US gas was praised and offered by Washington as an alternative to Russian exports, but this pledge will be hard to keep.

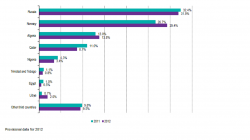

When it comes to EU dependence on Russian gas, one needs to look at the figures. Around 32% of the gas used domestically in the EU comes from Russia (largely using pipelines that cross Ukraine). Industries like car manufacture, metal production and other heavy manufacturing are reliant on Russian gas for power. Some Member States – generally in Eastern Europe – remain highly dependent on Russian exports. On the basis of figures alone, however, it will be no small task to end the EU’s energy dependence on Russian gas.

Moreover, US gas will have to overcome many obstacles before it can supply Europe. Firstly, the United States has no operational facilities to liquefy natural gas. They have 11 facilities capable of receiving liquefied natural gas (LNG) but some of these must be converted into liquefaction export facilities to meet the global market demand. So far only Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass liquefaction facility project has approval from the Energy Department and US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to become the largest US natural gas export terminal, beginning operation in 2015 or 2016. Furthermore, the path to approval for gas-export projects is complex when it concerns countries that do not have a free-trade agreement with the United States – which includes the EU. And any export projects approved after Cheniere will certainly not start LNG shipments earlier than 2017–2018. Secondly, transport of the LNG would require more than two million tanker trips a year to satisfy EU demand. And only about 400 of the gas tanks needed actually exist. Thirdly, the cost of shipping (for 6,000 km) would be huge. But before that happens, Europe will also have to spend years building vast gas pipe networks, liquid natural gas terminals and storage facilities. And after all that extra expense, what will happen to gas prices? The cost of gas delivered will almost certainly be higher than it is today.

Consequently, there is no American alternative to dependency on Russia in the short term. Other short-term alternatives also remain limited. In the immediate future and most probably until 2030, Europe will need Russian gas.

To conclude, the United States has no quick fix for the EU if the latter turns away from Russia. It is possible to start preparing now for the medium-term future of energy independence in order to be ready to seize all opportunities to fulfill this goal. The conclusion of the free-trade agreement currently under negotiation between the EU and the United-States could be a step in the right direction. Speeding up work on energy efficiency to reduce energy demand would be another one too, and not dependent on third parties.

EU-27 imports of natural gas – percentage of extra-EU imports by country of origin 2012.png – source Eurostat (data from May 2013)

The copyright of this commentary belongs to the Egmont Institute. It can be quoted or republished freely, as long as the original source is mentioned.

(Photocredit: zieak, Flickr)