Green Diplomacy Network – what is in a name?

In

Despite the great potential in combining national and community resources, the external representation of the European Union often remains fragmented. The Green Diplomacy Network has come to embody a unique pattern of successful cooperation between national and EU diplomatic structures on environmental issues overseas. This commentary briefly explores the network and discusses its applicability to further policy areas.

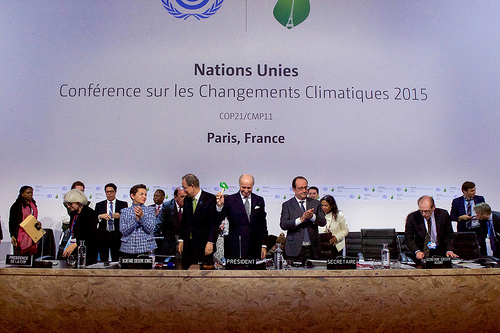

(Photo credit: US Department of State, Flickr)

*****

Green Diplomacy Network – what is in a name?

The external representation of the European Union (EU), with 28 member states plus the Brussels institutions, has a complex architecture. While the inauguration of the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the transformation of European Commission offices worldwide into EU delegations in December 2009 were meant to streamline external representation patterns, such hopes have only been partially attained. Despite a continuing series of national embassy closures abroad by EU member states, mostly spurred by shrinking budgets, many countries in the world host embassies from nearly the full complement of EU member states along with an EU delegation.

According to the Treaty of Lisbon, EU delegations and member state missions are expected to exchange information, carry out joint statements and cooperate in representing the EU externally. Whilst member states have made headway in grasping the potential of EU delegations in the recent years, the harmony envisaged by the drafters of the Treaty is yet to develop. Diplomatic structures of bigger member states, in particular, remain hesitant about sharing sensitive information with the EU delegation in-country, also often preventing it from acting as a central hub in implementing and coordinating EU policies on the spot.

Network diplomacy

One important but often overlooked initiative that has successfully combined the strength of EU delegations and national diplomatic structures is the Green Diplomacy Network (GDN). Launched by the European Council in 2003, the GDN was initially meant to promote the integration of environment objectives into the EU’s external relations through the creation of an informal network of experts based in national capitals. At its inception, each rotating presidency of the Council of the EU convened a GDN meeting in Brussels to inform other member states on the international environmental negotiations of the upcoming semester and to discuss the possibility of launching joint EU démarches on a certain environmental priority.

The entry-into-force of the Treaty of Lisbon on 1 December brought about some key changes for the network. To enhance continuity, chairing responsibilities were transferred from the Council presidency to the EEAS as of 2012. While GDN members gathering in the EEAS headquarters continue to select themes for démarches, the development thereof is now incumbent upon the EEAS and the relevant Directorates-General of the European Commission (DG Environment, Development and Cooperation, Climate Action etc). Once approved by members of the network in Brussels, EU delegations worldwide receive and undertake the démarche concerned at ambassadorial level in conjunction with like-minded member states.

Under the chairmanship of the EEAS, the network has come to embody a successful pattern of cooperation between national and EU delegations in third countries. This is because local GDN networks have also been created, allowing representatives from member state diplomatic structures to regularly consult each other under the lead of the local EU delegation. These local branches perform two key tasks. First, they promote the EU’s position on environmental issues through outreach campaigns and informal consultations. Such activities have generally been concentrated on the run-up periods of international climate summits, as was notably the case ahead of the 21st Conference of Parties taking place in Paris at the end of last year. Second, local GDN networks also serve to gather intelligence on the stances of third countries on environment policies with the aim of feeding additional insights back to EU negotiators. In this regard, the network focuses on the BASIC countries (Brazil, South Africa, India and China) which have a track-record of acting as a bloc in global climate talks, often advancing alternative positions to that of the EU. In light of the conclusions adopted by the Foreign Affairs Council on ‘European climate diplomacy after COP21’ on 15 February this year, the scope of activities to be undertaken by the network will most likely broaden. As such, the GDN will also be expected to extend its outreach activities from governments to international organisations (e.g. International Civil Aviation Organisation and International Maritime Organisation), civil society and green industries. In doing so, the aim will not only be to advocate climate change as a strategic priority but also to support the implementation of the Paris Agreement and to mobilise climate finance from private investors.

Successful precedent

In EU circles, the GDN has come to be seen as a successful example of how to combine the joint strength of EU diplomatic structures overseas in favour of more effective outreach and intelligence activities. At a time when emerging powers are becoming increasingly assertive in advancing their distinct interests on the international stage, the tasks performed by the GDN will be increasingly in demand. In addition to helping push forward action on sustainable development, informal local networks of EU and national diplomats could also represent an asset in advancing other principles and objectives guiding the EU’s external action. The GDN could thus serve as a model for other networks such as one on trade liberalisation, disarmament and non-proliferation and even on human rights. After all, most EU delegations worldwide are already staffed with at least one human rights specialist who could serve as a starting point for the formation of local networks also in this field. Engaging jointly in outreach activities and intelligence gathering in this domain would not only allow the EU to raise the profile of human rights globally but also to obtain broader support for its activities in the United Nations Human Rights Council.

Balazs Ujvari is a joint research fellow in the Europe in the World programme of the Egmont – Royal Institute for International Relations and the European Policy Centre in Brussels.